Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

Léon Creux’s Scroll Design: From Initial Failure to an Enduring Legacy

The HVAC/R industry isn’t short on tragic figures. There’s John Gorrie, whose ice machine showed a lot of promise but didn’t have enough financial backing due to the lucrative ice industry and the death of his business partner. While Gorrie may have died without seeing his vision reach the masses, he was ahead of his time, and his ice machine was still a major stepping stone in the world of compression refrigeration. Today, we’re going to talk about another man who invented a machine that we encounter almost every day in HVAC, but the world just wasn’t ready for it when it was first introduced: Léon Creux and his scroll.

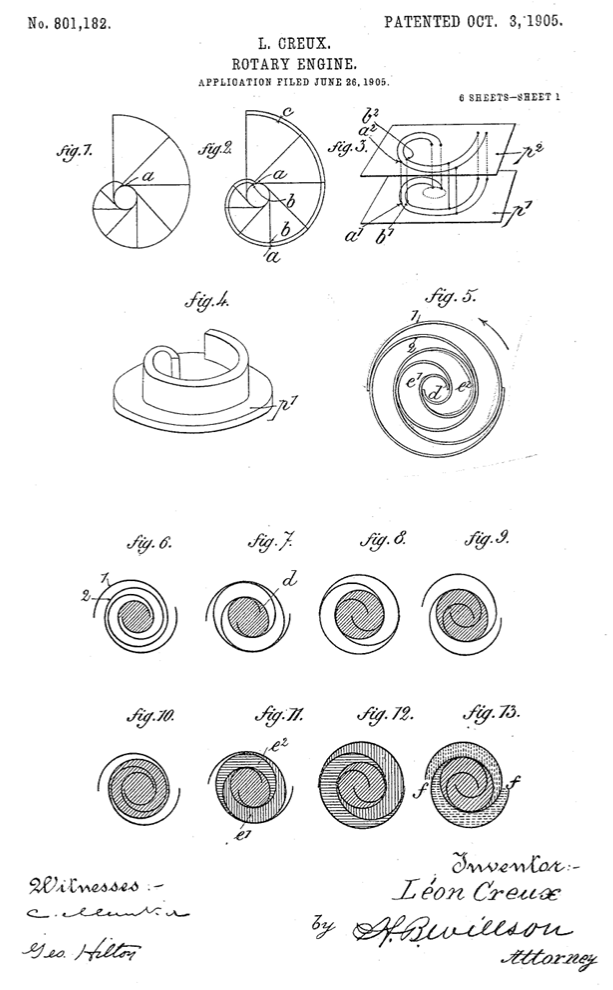

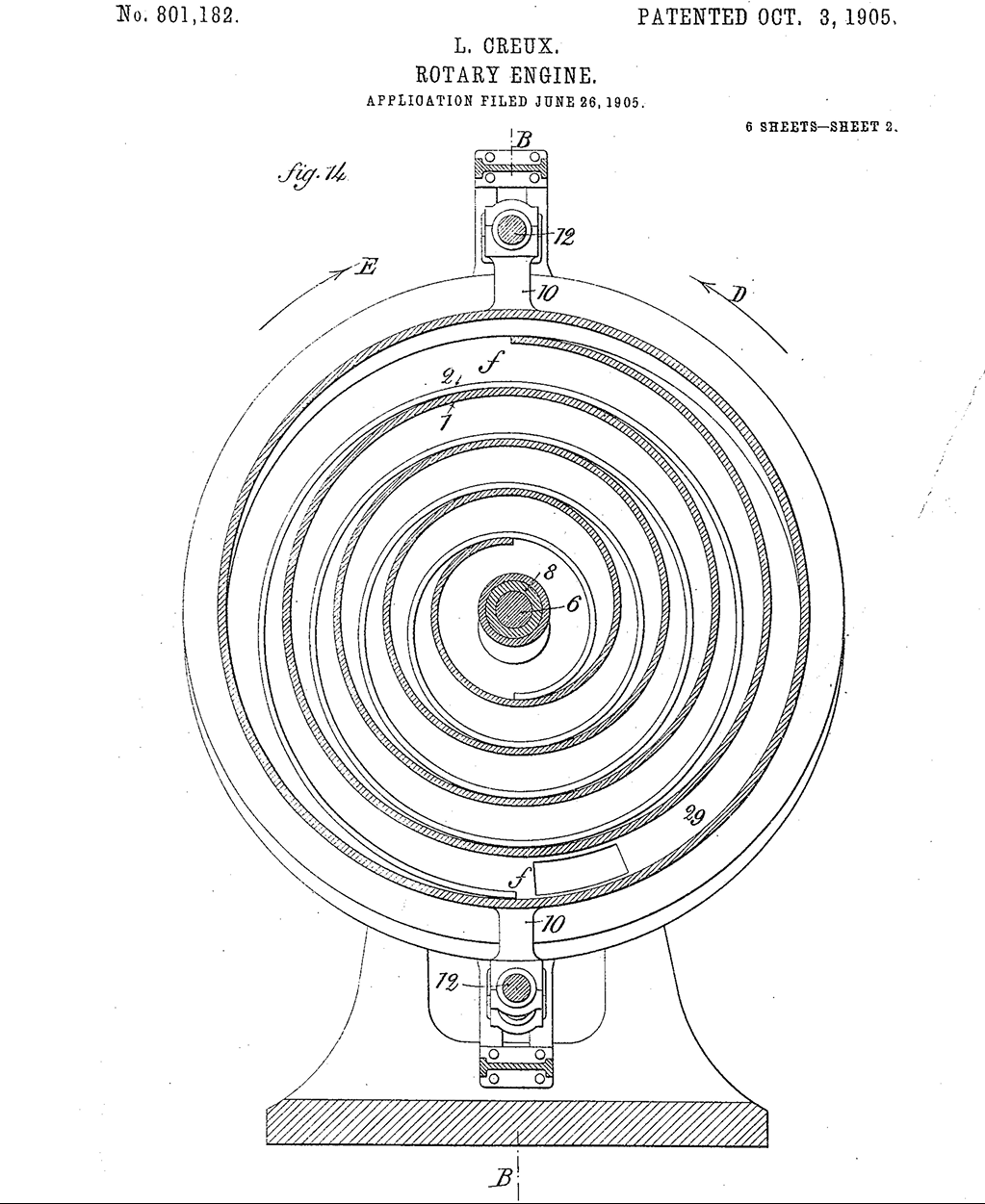

Léon Creux was a French engineer and inventor who came up with a rotary engine design in the early 1900s, which he patented in both France and the United States. This design consisted of two parallel plates with interlocking spirals and vapor inside, which closely resembles a part we see in many HVAC systems today.

Creux’s Invention

To be clear, Creux did NOT set out to invent the scroll compressor, just as John Gorrie didn’t try to invent the ice machines we see today. However, he did develop the precursor to it.

Creux patented his rotary engine design in 1905. The original intent was to use this rotary engine with steam to address the needs of society at the time, as steam power dominated at the beginning of the 20th century. This invention had two plates with spiral bands and an entry point in the center for an “elastic fluid under pressure.” Of course, that fluid was steam, not a refrigerant like R-22 or R-410A (which didn’t exist at the time).

As that fluid expanded, it would exert a force on one of the spirals, causing it to move in a circular fashion relative to the other spiral. (The GIF at the beginning of the article shows what that motion looks like in a scroll compressor.) That fluid would exit at the periphery of the spiral assembly for continuous operation.

That sounds like the opposite of a compressor; a compressor compresses fluid, and Creux’s invention allowed the expansion of fluid to drive the motion. However, in the US patent, Creux also stated that his invention “may of course be used also as a pump for compressing an elastic fluid.”

Creux’s invention could have one fixed spiral band and one moving spiral band, like a modern scroll compressor, or it could support two moving spiral bands.

Not So Fast

On paper, Léon Creux’s invention seemed like something that had the potential to become an engineering staple in a variety of applications. Unfortunately, “on paper” is the key term here; his invention was limited by the constraints of the times. The casting and machining technology of the early 1900s was nowhere near advanced enough to make his patent into a viable prototype, let alone refined models that could eventually be deployed on a large scale.

Creux’s design required the spirals to have very tight tolerances, which the metal casting technology wasn’t precise enough to create. A working prototype could not be built without leaks, which defeated the purpose of the entire design.

Though the patent existed, the idea remained just that. The technology to make it a reality simply didn’t exist. Reciprocating and rotary screw compressors also filled the void for compression and positive-displacement pumping technology, leaving little need for anyone to consider Creux’s design for that use. Creux died in 1938 without ever seeing his dream come to fruition.

The Comeback

More than 30 years after Creux died, and more than 65 years after his original patent was filed, physicists started taking an interest in scroll designs once more. In the early 1970s, physicist Niels Young created a scroll design much like Creux’s but for the primary purpose of positive displacement vapor compression. He took an interest in the project around 1972, and some physicists with Arthur D. Little (ADL) began working on the technology in 1973 as well.

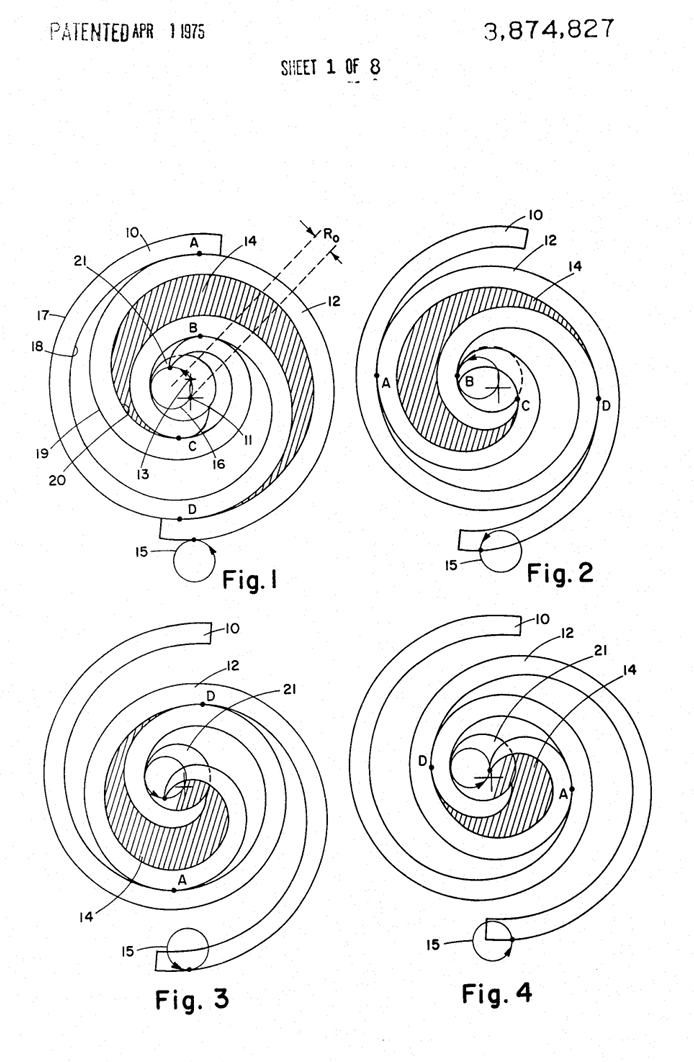

In 1975, Young filed a patent for his “Positive displacement scroll apparatus with axially radially compliant scroll member.” This patent has a lot in common with Creux’s, but it addresses axial and radial compliance, which is a key part of scroll compressor technology.

Compliance refers to the scroll’s adjustability relative to its radius (the horizontal distance from the center to the outside edge) or axis (the vertical line on which both scroll plates are centered). THIS tech tip has some more information, but in a nutshell, radial and axial compliance refer to the contact between the scrolls as the orbiting scroll moves horizontally and the ability for the scrolls to pull apart and unload, respectively.

In the 1970s, Young and ADL also had access to casting and machining technology that wasn’t available in the early 1900s. The spiral design, which was too complex for the technology available during Creux’s time, was able to be created by machines that relied on numerical inputs and computers for far more precise design features. The leaks that plagued early attempts to build Creux’s design were a problem no more.

Spreading to the Masses

While individual people like Léon Creux and Niels Young were the brain power behind these scrolls, it was corporations that applied and evangelized the scroll technology.

The scroll compressor was first mass-produced for cars. Sanden started manufacturing scrolls for use in automobile air conditioning in 1981. Scrolls began being used in air conditioning for buildings in 1983 when Hitachi launched a room air conditioner with a hermetic (fully sealed) scroll compressor.

To [probably] nobody’s surprise, it was Copeland’s use of scroll compressors in heat pumps that made the scroll compressor’s popularity explode. In 1987, Copeland debuted this technology in the residential air conditioning and heat pump market, extending to light commercial in 1990 and refrigeration in 1992.

Inspiring New Developments

Daikin was another early adopter of scroll compressor technology, but the Daikin team didn’t just hop on the bandwagon; they began to explore new possibilities. In the 1990s, Daikin and Hitachi began using scroll compressors in the development of inverter-driven systems, which could ramp compressor speeds up and down based on the needs of the space. HERE is a short podcast about how inverter systems work.

Copeland, too, used scroll compressors as they innovated and pursued advancements in variable-speed technology. Copeland also developed vapor injection systems, which could reduce compression ratio and boost efficiency. Vapor injection started as a commercial refrigeration development, but we now see it in scroll compressors that can handle 2–25-ton HVAC systems, including VRF. Roman Baugh has a video walking through the vapor injection process HERE. He also got to see one of Copeland’s innovative vapor-injection compressors at AHR 2025, which you can see HERE.

To This Day

In the present day, scroll compressors are everywhere. They’ve been made to meet the design requirements of low-GWP refrigerants and even CO2 in the refrigeration world. Industry titans have built on a humble French physicist’s idea and developed compressors that can load match and run more efficiently than anyone in the 1980s could have ever imagined, let alone anyone in the early 1900s.

If only Creux knew that his humble idea would become the prevailing compressor technology over a century later…

The Merits of Dreaming Big, Even “Too Big”

Léon Creux came up with his idea when there was no way for him to make a viable prototype, let alone prove if it could even work. But he still filed the patent. If he hadn’t done that, we likely would not have the variable-speed compressors, vapor injection, and inverter technology we see today.

Creux never saw his idea become anything more than a patent and some diagrams. He had no idea it would revolutionize an entire industry—one that didn’t even exist at the time he filed his patent (at least not on a commercial scale).

We don’t know whether he felt despair or regret or simply moved on. Most of us probably didn’t even know he existed and was such an important figure for HVAC/R until today! But now that we’ve explored the history of Léon Creux's invention and the scroll compressor, we can confidently say that he was an innovator who chased the impossible, and it paid off. Maybe not in his lifetime, but it paid off.

Our legacies are not decided by our actions but by what others take away from our actions. Creux is one such example of a person whose brilliance and dreams went relatively unnoticed during his lifetime, but our industry wouldn’t have been the same without him.

The moral of Léon Creux’s story—apart from the fact that scroll compressors are cool and have come so far—is that impossibility is not a death sentence for brilliant ideas. Creux received no accolades for his invention in his lifetime, but those don’t matter in the grand scheme of human innovation. What matters is that we speak up and share our ideas during our lifetimes—and don’t fear dreaming big!

Even if you may never get to see an idea take off, that doesn’t mean it’s not worth sharing or believing in. After all, a legacy is determined by our lasting impact on humanity—what others take away from our ideas and actions, not just how much recognition we receive for our work or ideas. The scroll compressor we see every day is one such example; even if you didn’t know the name “Léon Creux” until today, that doesn't change the fact that HVAC equipment and service wouldn’t be the same without his contribution.

Comments

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In