Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

Dedicated Dehumidifier vs. Electric Reheat Dehumidification – Who Ya Got?

This dehumidification tech tip was written by Tim De Stasio. He originally published it on his website, which you can visit HERE. Thanks, Tim!

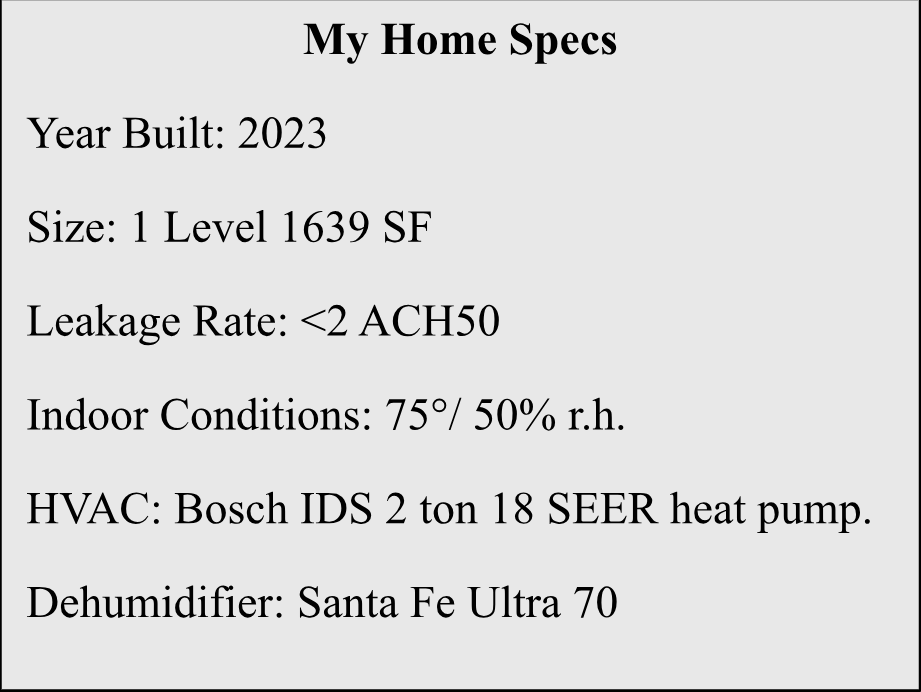

In March of 2024, I set out to better understand the cost of ownership and return on investment for two dehumidification strategies: a dedicated dehumidifier versus using electric reheat dehumidification from my heat pump. It wasn’t a perfect scientific test by any means, but I can confidently make some qualifying statements about the principles and trends I observed.

Some in our industry have had great success using a communicating inverter heat pump and staging electric reheat (like what Carrier Infinity offers) and claimed the higher energy use would still be cheaper in the long run than installing a dedicated dehumidifier. Many of us HVAC performance nerds were unsure of this approach for southern humid climates, so I set out to find out for myself in my southern climate.

In This Corner: A Dedicated Dehumidifier

The dedicated dehumidifier uses refrigerant similar to an air conditioner to condense moisture out of the air. It also re-heats the air with its own condenser coil. This hot gas reheat slows down the overcooling process that often happens using a refrigerant-based dehumidifier.

I selected the Bosch IDS split heat pump, despite some claiming they didn’t dehumidify well. Others, like Jim Bergmann, were enjoying good results after extensive setup and observation. I was convinced that I, too, could make my Bosch a moisture monster too.

The two systems work in unison, controlled by my Ecobee thermostat and the HAVEN IAQ environment.

In The Other Corner: Electric Reheat Dehumidification

Electric reheat dehumidification uses the heat pump compressor you already have. But since you can’t dehumidify without first cooling it, there are times when the space temperature could drop below a comfortable level. When that happens, the electric strips, which are downstream of the cooling coil, are staged to reheat the air during dehumidification cycles. You’re heating and cooling the air simultaneously, allowing dehumidification without a separate dehumidifier.

Electric reheat dehumidification is only a factory option on a few heat pump models, such as the Carrier Infinity. To test this on my Bosch, I used a Wi-Fi relay pack and created a series of automations in If This Then That (IFTTT).

Rules of the Match

For the 2024 cooling season, I developed a way to test both strategies. Every month, from the 1st to the 15th, I’d let my Santa Fe dehumidifier and Haven IAQ control the humidity in my home. From the 16th to the end of the month, I’d disengage those controls and engage my re-heat dehumidification setup. Then, I’d average my daily energy usage and normalize my bills as if I’d run each strategy for the entire month. Every month from March to October, I tracked my energy use, cost, and simulated utility bills. To be fair, both strategies maintained the same indoor conditions: 73–75°F and 50–55% RH.

It wasn’t a perfect test. In early March, the dehumidifier enjoyed the advantage of cooler, drier weather, so it didn’t work as hard. But in late October, the reheat strategy had its turn with similar weather. I wasn’t testing each strategy at the same time, but rather during two different periods each month.

Data and Observations

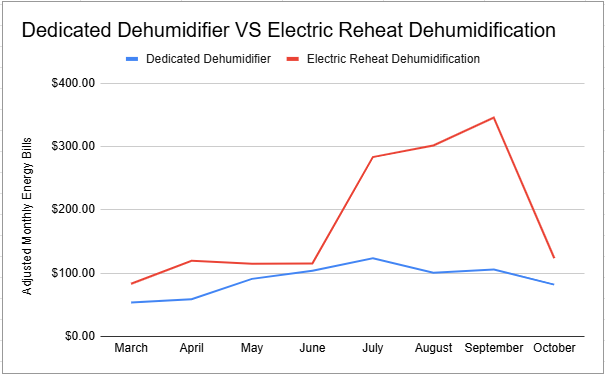

Difference in Energy Cost

During March to October 2024, I would’ve paid approximately $768 more in energy had I used only reheat dehumidification. Comparing that to the installed cost of a basic whole-house dehumidifier, which starts at $5,000, it would take 6.5 years of reheat dehumidification (at best) to pay for the separate dehumidifier. Will a dehumidifier last at least 6.5 years? We hope so. Santa Fe offers a 5-year replacement warranty on their units.

Low Sensible, High Latent Periods are Frequent

During peak outdoor design temperatures, there was enough sensible load for my cooling cycles to control humidity without the need for either dehumidification strategy. But every hot summer day ends with a muggy summer night. The outdoor temperature drops to the mid-70s at night, but the humidity stays above 70°F dew point. The AC doesn’t run as much.

In late summer, we saw numerous tropical events that dumped moisture for days. I noticed a lot of reheat during those times because I didn’t have the sensible load, but there was still plenty of latent load. That’s one of the things that makes southern climates much more challenging because our buildings don’t dry out when the weather starts to cool.

The Bosch Actually Dehumidifies Well

Some have criticized my experiment claiming my Bosch doesn’t dehumidify effectively, therefore a reheat strategy using it would naturally be very inefficient. The key to effective reheat dehumidification is a heat pump that can run at a lower sensible heat ratio (SHR) and remove more moisture. If the SHR is too high, it's a simple sensible-for-sensible tradeoff and wastes energy.

The Bosch uses an inverter-driven compressor that varies its capacity to maintain a constant indoor coil temperature of around 44°F in “enhanced cooling mode.” The air handler is a 2-speed unit, and by varying the airflow, the compressor self-adjusts. My Ecobee thermostat offers reverse staging, which allows the system to back down from stage 2 to stage 1 instead of staying in stage 2 until the thermostat satisfies.

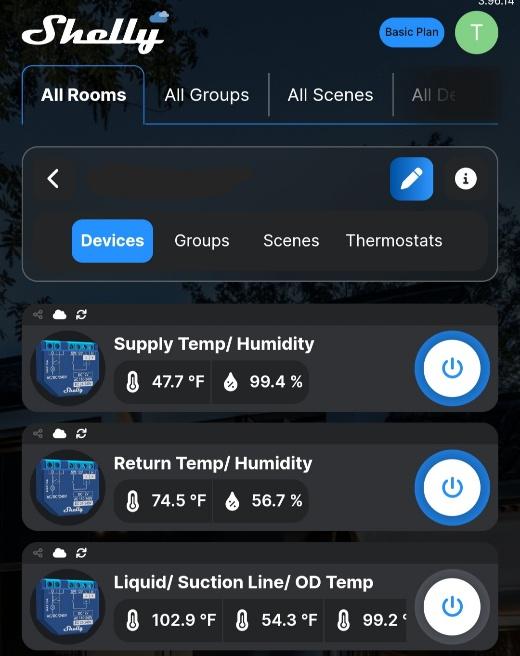

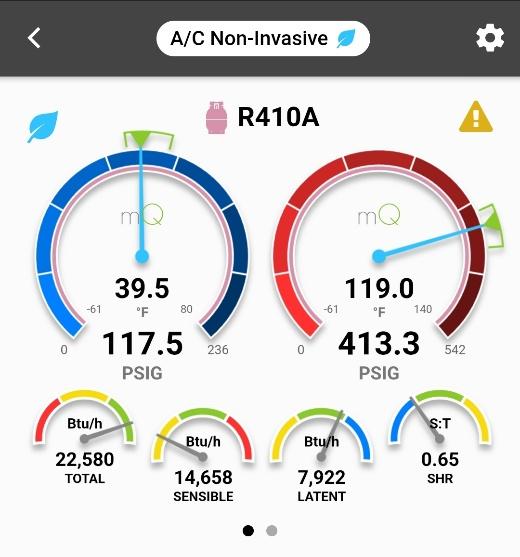

I tracked my Bosch’s performance using my own air temperature/humidity and pipe temperature sensors from Shelly Automation. This method gave me the data needed to manually input into measureQuick to calculate my delivered sensible and latent capacity as well as sensible heat ratio.

As can be seen below, during the Bosch’s reverse staging cycle measured on a hot July day, it enters into a robust dehumidification cycle with a SHR of 0.65 (I observed even lower). The indoor coil actually drops well below the 44°F that Bosch claims. That's close to the latent performance of a communicating system, such as the Carrier Infinity in dehumidification mode.

Screenshots of real-time performance entered into measureQuick showing the Bosch’s robust dehumidification ability.

Setpoints Matter

In the month of June, I accidentally set my reheat dehumidification setpoint to 60% instead of 50% RH. I noticed a sizable savings in energy because my compressor didn’t run as long, so my reheat didn’t have to either. It’s like squeezing an orange; if you’re trying to get the last few drops out, you expend a lot of energy for very little gain. Running a humidity setpoint of 50% or lower is like squeezing the orange very hard. Being willing to keep the house at the edge of the “danger zone” of 60% RH or 60°F dew point makes reheat dehumidification more desirable.

AC has the Capacity (as long as it’s running)

I noticed my dedicated dehumidifier struggled during extreme humidity, or if we had company over on a humid day and doors were opening a lot. But after a few hours, it still recovered. But my heat pump had more than enough capacity to maintain humidity during these periods. That’s a win for reheat dehumidification.

Every House is Different

In my HVAC consulting business, I notice that every home behaves a little differently. Some will need more dehumidification, some less. The climate, envelope tightness, ventilation strategy, equipment and controls installed, utility rates, and occupant comfort levels all drive the cost difference between these two strategies. Anyone claiming to understand this completely from only a few case studies is drawing conclusions on too small a sample size.

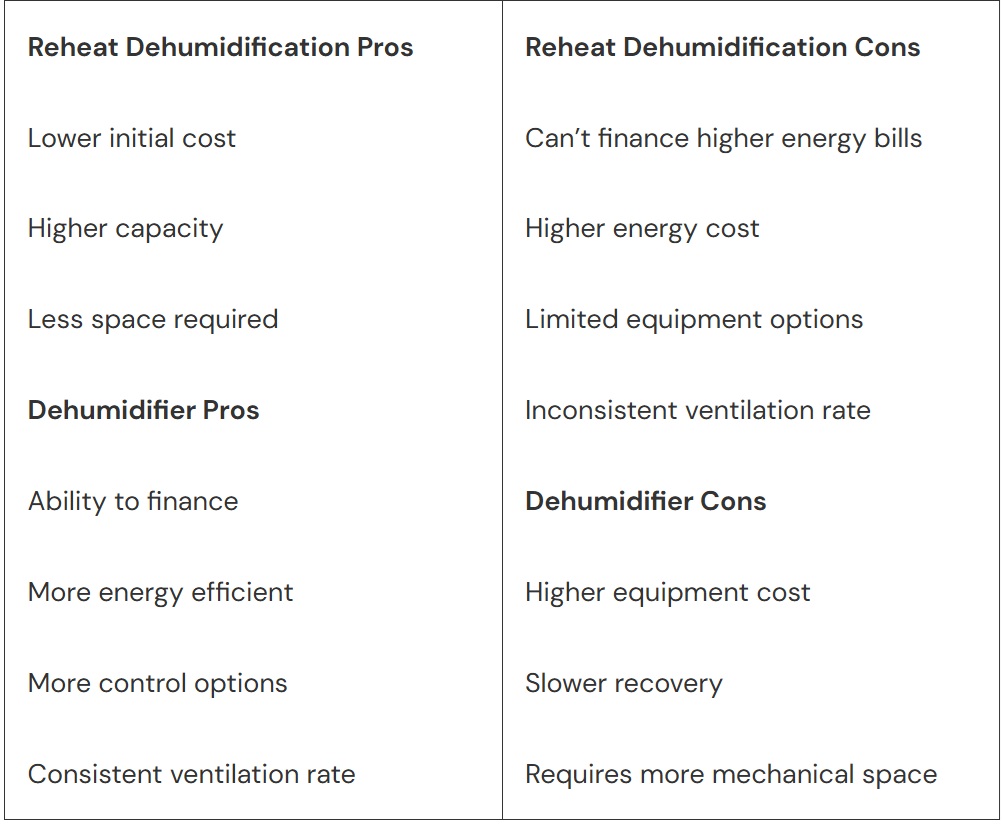

The Winner, By Split Decision

Both strategies have pros and cons, and either could’ve worked in my house. But I can see a scenario in a humid climate, with a leaky house or one that ventilates a lot, where the comfort habits of the occupant could result in shockingly high energy bills. People can finance a dehumidifier over a few years, but they don’t have the option to finance high utility bills in perpetuity. As contractors, we should make sure our clients fully understand their options. Personally, I don’t like the thought of explaining to my customers why, in the summer, their utility bills will now be $350/ month—all in the name of lower indoor humidity.

Also, a dehumidifier works with the existing system as an add-on. Conversely, the communicating systems that offer reheat dehumidification are expensive, much more expensive than a standard HVAC unit. What if my customer is not ready to replace their system yet?

There are a few thermostat choices that offer reheat dehumidification for existing 24V systems. Of these, include the Honeywell TH8300 series in commercial mode. The IFTTT automation that I created is not really a contractor option.

If fresh air is offered, a ventilating dehumidifier offers a constant ventilation rate and is not dependent on the air handler’s blower speed. On the other hand, a communicating air handler must choose whether to prioritize humidity control OR fresh air ventilation.

For these reasons, I think that a dedicated dehumidifier is a better strategy than reheat dehumidification in southern or coastal climates. It wasn’t a knockout, but rather a points victory.

There is no free lunch in building science. Humidity control costs money, regardless of the strategy used. If your client can’t afford the upfront cost of a dehumidifier, you could install a thermostat capable of reheat dehumidification using the heat pump they already have and see if the variables are in their favor or not. And you should be testing and offering envelope and duct improvements whenever possible to lower their moisture load.

For my home, the yearly cost of reheat dehumidification was $768. Your client’s home will be a different number. And while I’m happy I did this test, I'm proud of what I learned, and I'm content knowing what I can’t predict, what I’m most happy about is: this year, I think I’ll spend $768 on something else.

—Tim De Stasio

Comments

Thanks Tim. Could you tell us more about your Shelly Automation setup, please? Are you using multiple Shelly Plus Add-Ons? Thank you.

-Hap

Thanks Tim. Could you tell us more about your Shelly Automation setup, please? Are you using multiple Shelly Plus Add-Ons? Thank you.

-Hap

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In