Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

A Field Guide to Conductors for HVAC Techs

HVAC work is never just “HVAC” work. One minute you're brazing copper, and the next you're troubleshooting a blown fuse in a disconnect or running a new whip to a condenser. Because our trade is so varied, you never know what you're going to find when you open a service panel or crawl into an older attic. That’s especially true in a state like Florida, where we see some interesting legacy wiring.

Having the proper wiring is important for equipment functionality and safety. We may come across wires that are too small, the wrong type for the job, or a fire hazard waiting to happen.

Here is your field guide to understanding the wires that power our equipment, identifying legacy hazards, and handling wiring issues like a pro on the job site.

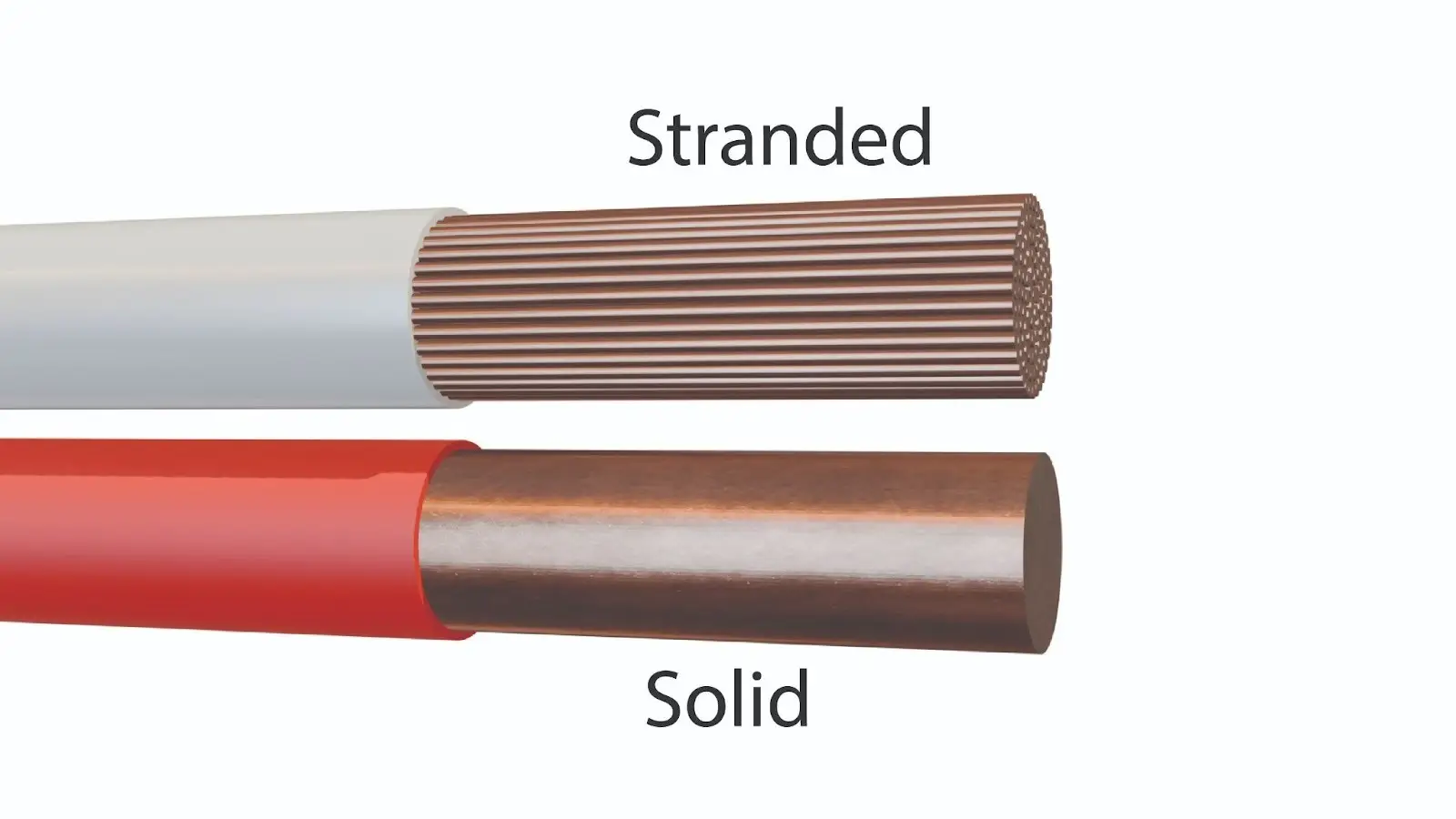

Solid vs. Stranded: It’s All About Flexibility

You’ve got a roll of thermostat wire and a roll of THHN for a whip. One is solid, one is stranded. Why?

Solid wire is rigid. It’s great for permanent terminations that don’t move, like the back of an outlet or inside a wall. Stranded wire is flexible. We use it in whips and motors because HVAC equipment vibrates. If you used solid wire to power a compressor, the constant vibration could eventually snap the conductor.

The “Ghosts” of Florida Past: Legacy Wiring

In Florida, we work on houses built across several decades—from new houses built in the 2020s to historic homes in the late 1800s. If you’re doing a changeout in a home built before 1980, keep your eyes peeled for these three things.

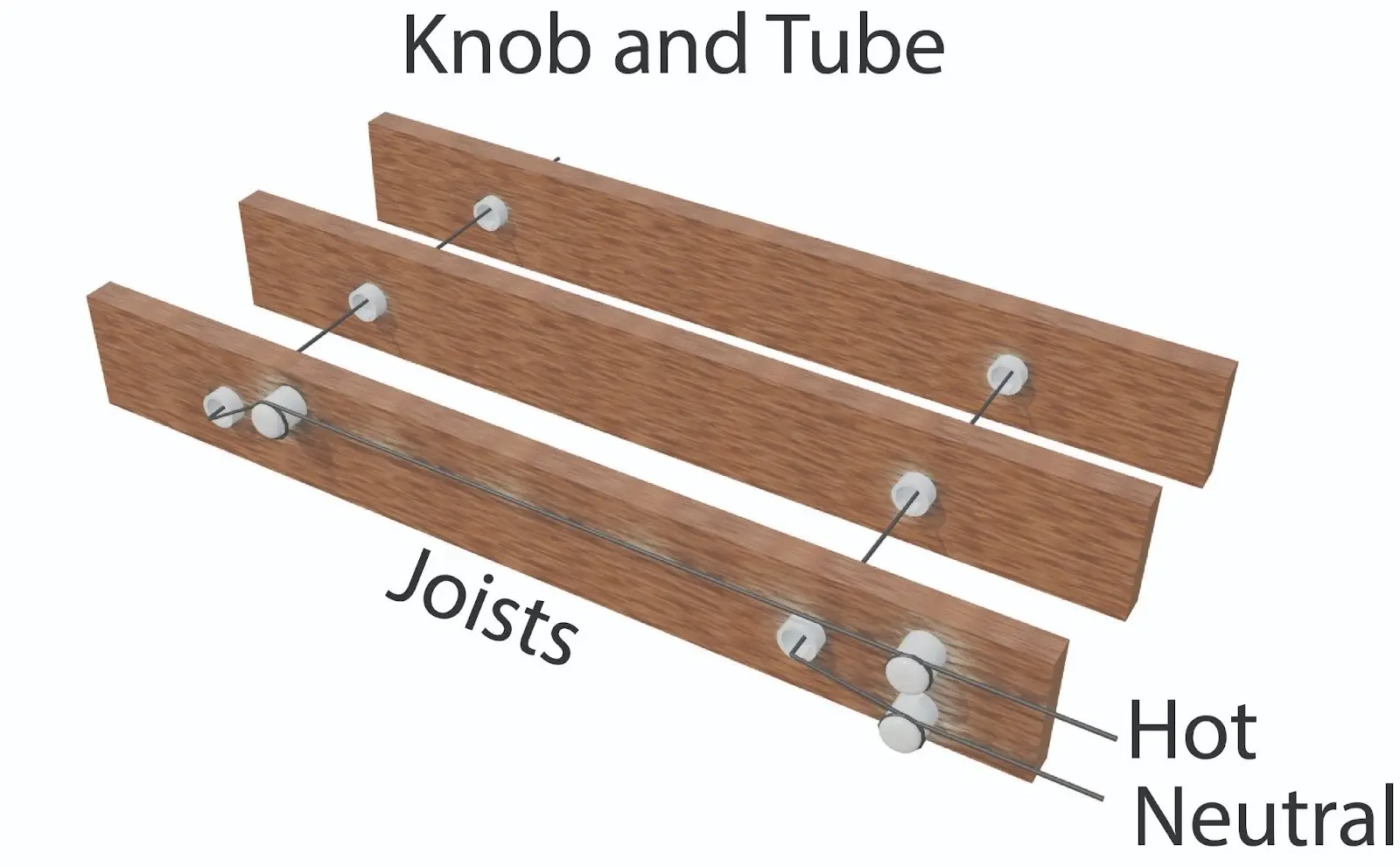

1. Knob & Tube (Pre-1940s)

You usually won’t find this powering an A/C, but you might see it running through the attic while you’re doing ductwork. It uses porcelain knobs to hold the wire and tubes to pass through studs. It has no ground, and the insulation is often crumbling. Don't touch it.

2. Cloth “Rag” Wiring (1940s–60s)

This stuff looks like a shoelace. It’s rubber insulation wrapped in a fabric braid. Over time, the rubber dries out and cracks off, leaving bare copper exposed. If you move a cloth wire in an air handler closet to make room for a new unit, the insulation might flake right off in your hand.

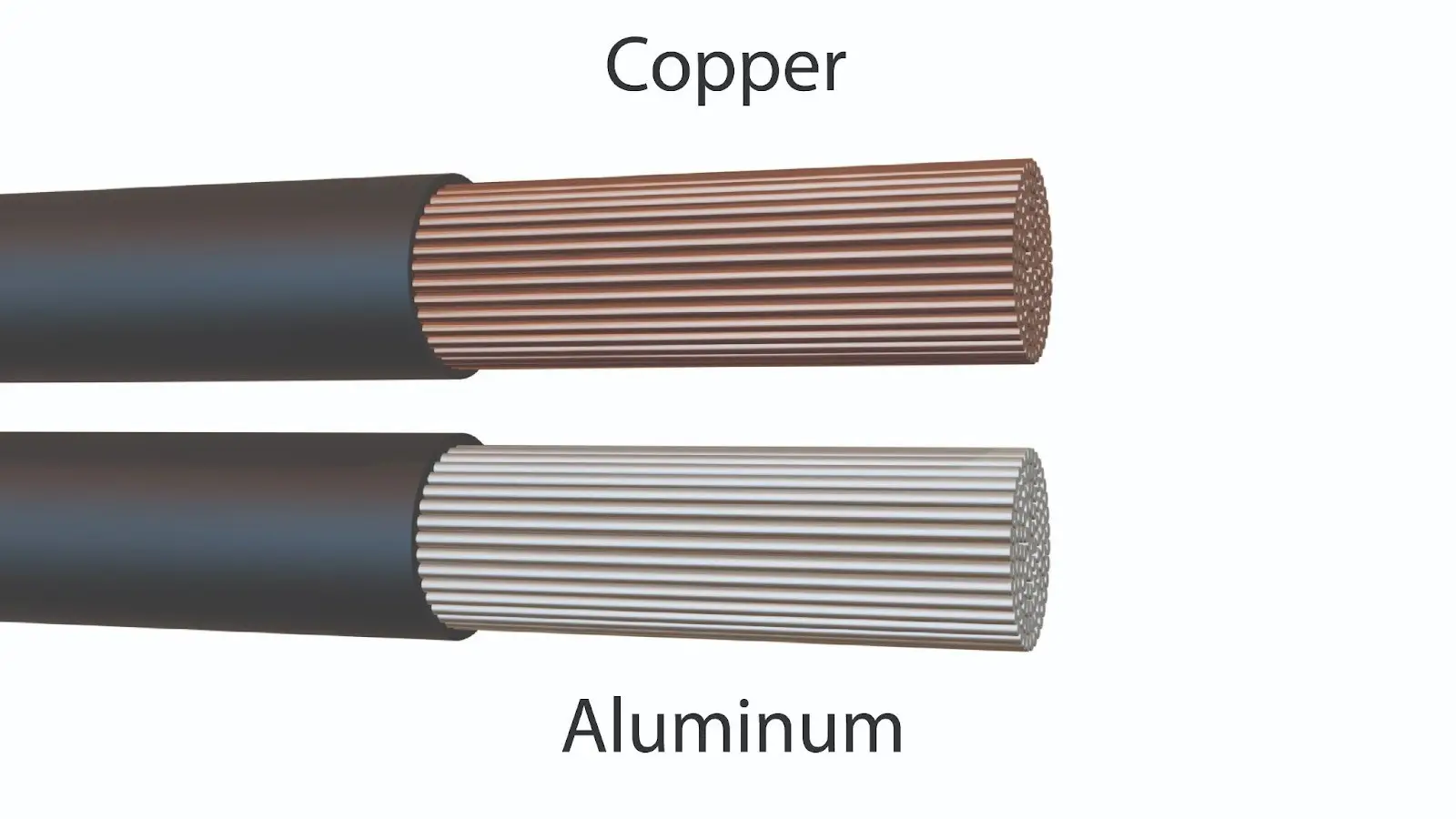

3. Aluminum Branch Wiring (60s–70s)

This is the big one for HVAC techs. During the Vietnam War era, copper was expensive, so builders used aluminum for small branch circuits. The problem? Aluminum expands and contracts differently from copper. It loosens under screws and creates arcs—a major fire risk.

If you open a disconnect or a sub-panel and see silver wire on a 20A breaker, stop. You cannot just crank it down. It needs special “CO/ALR” rated lugs or proper remediation.

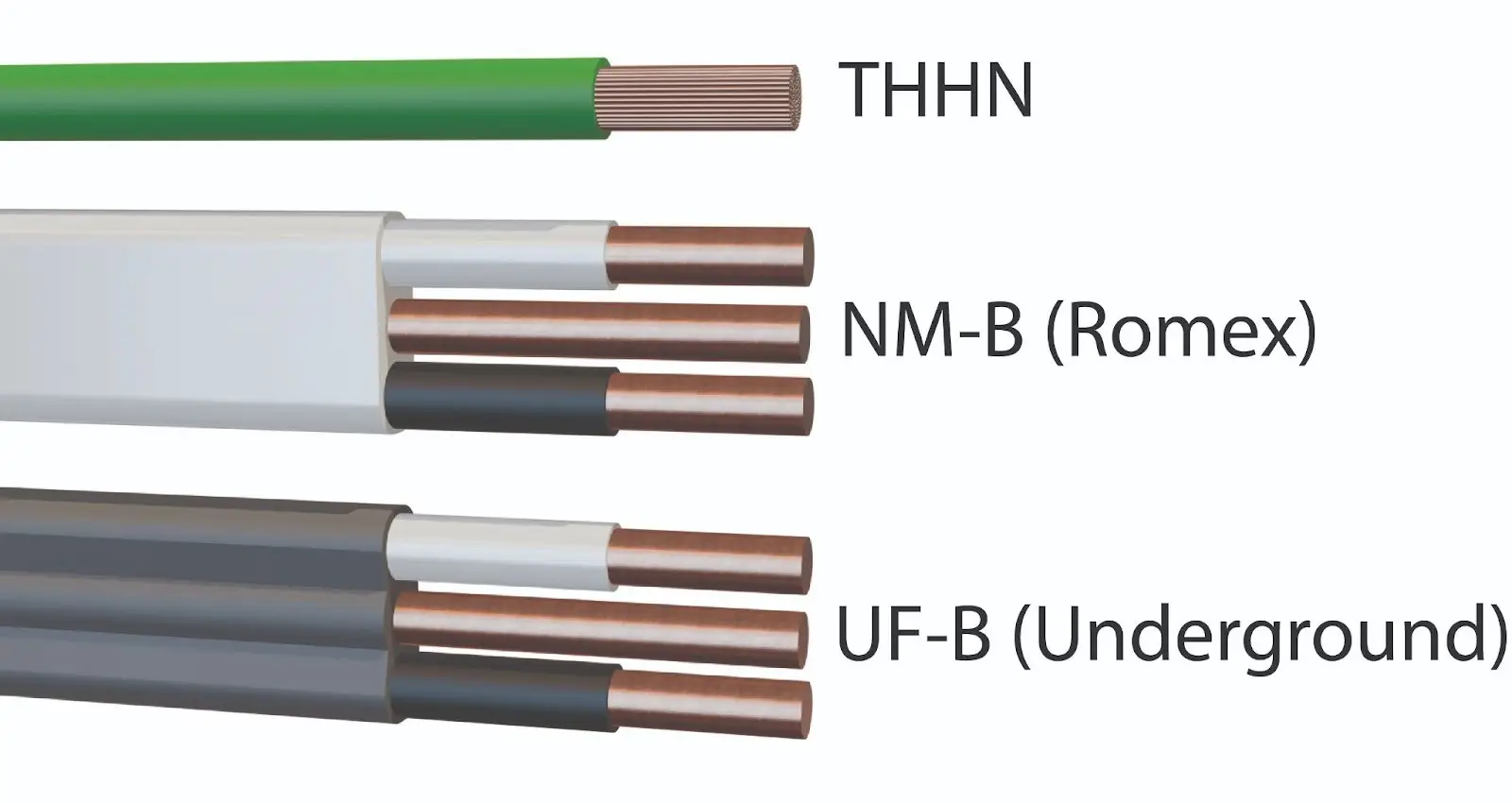

Know Your Jacket: Romex, UF, and THHN

You can't just grab any wire off the truck. The insulation dictates where you can install it.

- THHN/THWN: This is the individual wire we pull through whips and conduit. It’s rated for wet or dry locations and handles heat well (90°C).

- NM-B (Romex): This is for Indoor/Dry use only. You cannot run orange Romex inside a liquid-tight conduit to a condenser outside. The paper filler inside absorbs moisture and will rot the wire.

- UF-B (Underground Feeder): This looks like gray Romex, but the plastic is solid around the wires. It’s designed for direct burial or wet locations.

Temperature Ratings

There is a huge misconception out there that if a wire says “90°C” on the jacket, you can run it that hot. If you do that in HVAC, you’re going to melt components.

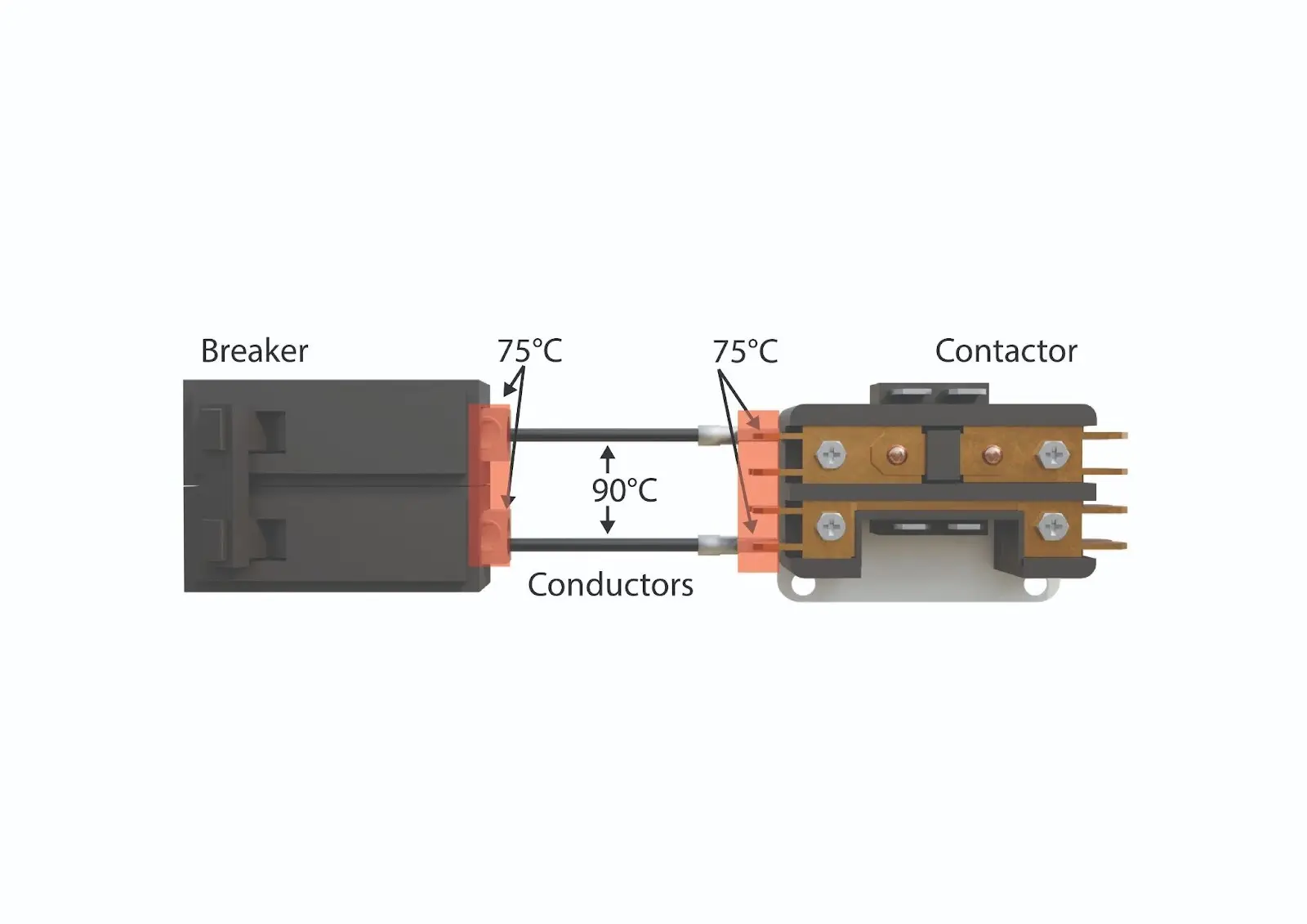

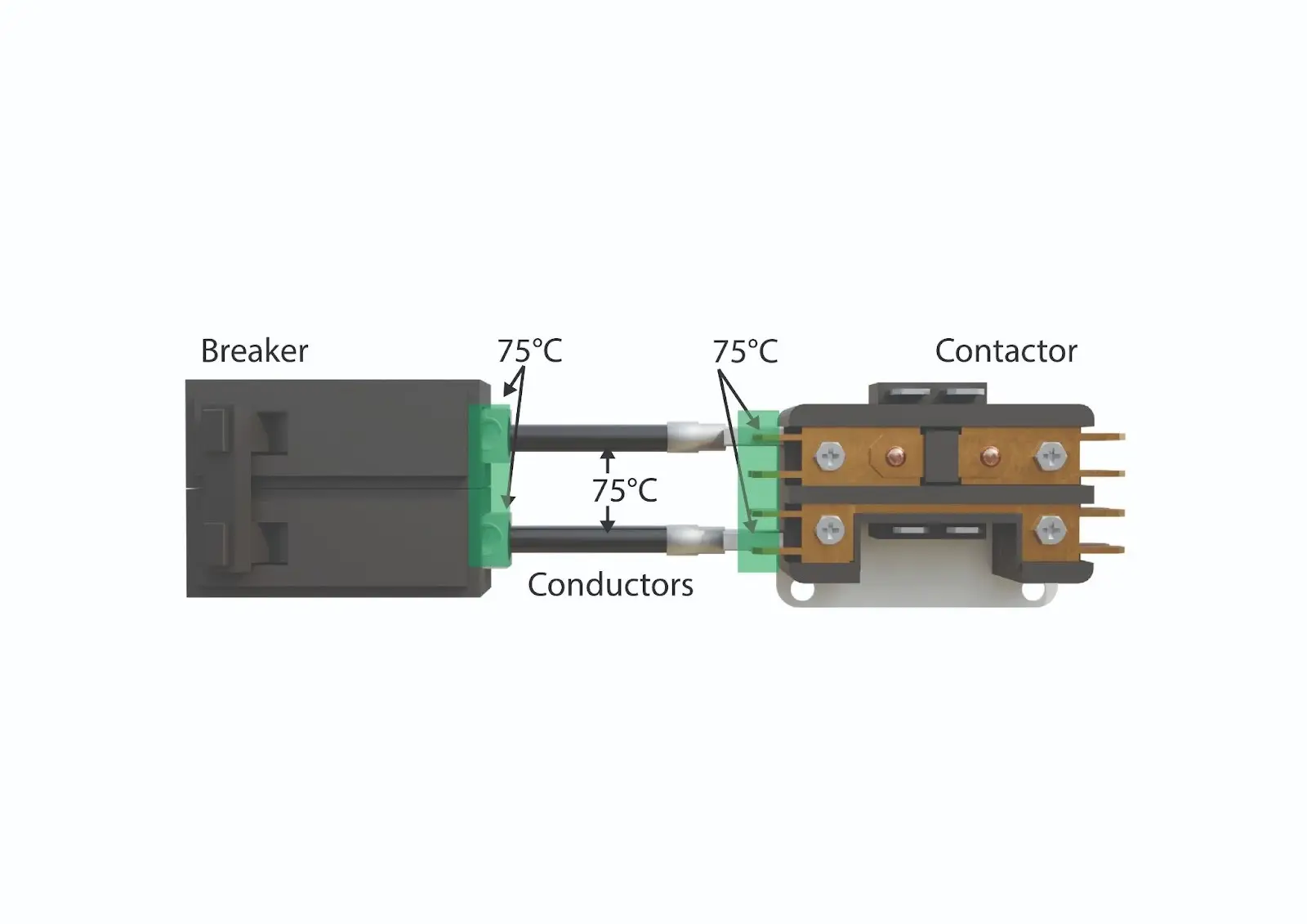

An electrical circuit is a chain. The breaker, wire, and equipment lugs are all links in that chain. If your wire is rated for high heat (90°C) but your contactor lug is only rated for medium heat (75°C), you have to treat the entire circuit as if it’s rated for 75°C.

Why do wires get hot?

Every wire has internal friction, called resistance. When you push amps through copper, that friction creates heat.

The “Temperature Prediction” Chart

Think of the NEC ampacity tables as a prediction tool. They tell you: “If you push 55 amps through this #8 wire, it is going to get hot.

The wire insulation can handle that heat. It won't melt. But your contactor will.

Most HVAC contactors and breakers have lugs rated for 75°C. If you bolt a 90°C wire into a 75°C lug, the heat travels from the wire into the lug, and eventually, the lug fails.

The Fix: You don't lower the amps; you upsize the wire. A thicker wire has less resistance, so it runs cooler (say, 60°C or 75°C) even with the same load, which keeps your lugs safe.

(Note: These images are exaggerated for illustration purposes and do not represent real sizes.)

The HVAC Rule of Thumb

To keep it simple and safe:

1. Stick to the 75°C Column: Since almost all commercial HVAC terminations (chillers, RTUs, disconnects) are rated for 75°C, sizing your wire to this column is the safest bet. It ensures the wire stays cool enough not to damage the equipment.

2. The “Small Stuff” Rule (NEC 110.14): For circuits under 100 amps (or wire 14 AWG to 1 AWG), the code assumes your terminals are rated for 60°C unless marked otherwise. Note: NM-B (Romex) is always stuck in the 60°C column.

3. Trust the Nameplate: The manufacturer has already done the math. If the unit says “Minimum Circuit Ampacity (MCA): 34 Amps,” size your wire for 34 amps using the 75°C column (unless it's Romex).

Bottom Line: Don't let the “90°C” on the wire jacket fool you. Upsize your wire to keep the temperature down and your terminals safe.

Sizing at a Glance: The Romex Rainbow

Since the early 2000s, Romex jackets have been color-coded. This is a great “sanity check” for HVAC techs walking a job. If you see a 3-ton condenser (which usually needs a 30A circuit) fed by a yellow wire, you immediately know something is wrong.

These colors are as follows:

- White: 14 AWG (15 Amps)

- Yellow: 12 AWG (20 Amps)

- Orange: 10 AWG (30 Amps)

- Black: 8 AWG or 6 AWG (40–60 Amps)

Memorize the colors. If you see a yellow wire on a 30A breaker, you’ve got a problem.

Note: A gray jacket usually means UF cable (underground), not a specific size. Read the print!

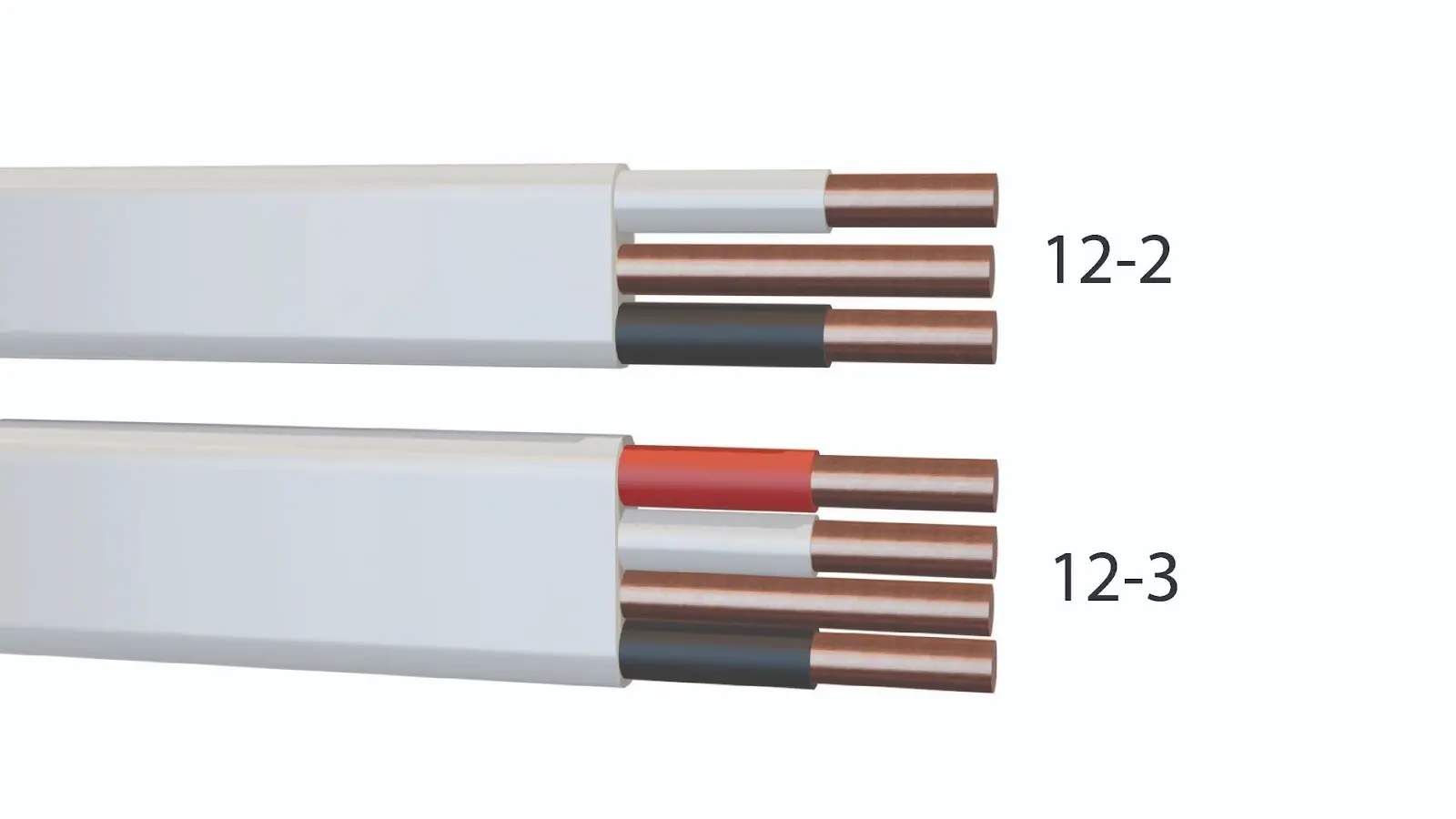

Counting Conductors: 12/2 vs. 12/3

When you ask for “12/2 wire,” you are asking for two insulated conductors (hot, neutral) plus a ground. If you need a neutral and two hots (like for some dryers or ranges), or you are running a 3-way switch, you need 12/3 (black, red, white + ground).

12/2 (top) has 2 wires + ground. 12/3 (bottom) adds a red wire for an extra hot or traveler.

Commercial Work: Respect the “BOY”

In residential (120/240V), we are used to black and red being hot. But if you step onto a commercial roof with 480V 3-phase RTUs, the colors change. We use the acronym “BOY” to remember the phasing.

- Brown (Phase A)

- Orange (Phase B)

- Yellow (Phase C)

- Gray is the neutral (instead of white)

Conclusion

Understanding electrical conductors doesn't just keep you safe; it helps you spot issues that others miss. Whether it's catching an undersized wire on a compressor or identifying dangerous aluminum wiring in a disconnect, knowing your wires is part of being a true professional.

Be safe, test before you touch, and keep learning.

—JD Kelly

Comments

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In