Get Tech Tips

Subscribe to free tech tips.

I’ve Done It This Way for 20 Years – And That’s the Problem

Every trade has its favorite phrases. One of the most common in HVAC goes something like:

“I’ve been doing it this way for 20 years and never had a problem.”

When you hear that—or when you catch yourself saying it—it’s worth stopping to think. Usually, what that sentence really means is:

“I’ve been doing it this way for 20 years and never had a problem… for me.”

The hidden truth is that a lot of shortcuts don’t come back to bite the installer or service tech. They come back to bite the customer—sometimes immediately, but more often years down the line. The customer pays the higher utility bill. The customer lives with reduced comfort. The customer’s system dies years earlier than it should.

Let’s walk through a few examples where “it’s fine” really means “it’s fine until the customer pays for it.”

Flowing Nitrogen While Brazing

Back in the mineral oil days, a lot of techs got away with brazing without flowing nitrogen. The inside of the tubing would oxidize, sure, but mineral oil didn’t react much with the copper oxide. The scale stayed stuck to the pipe walls and didn’t cause big headaches.

POE and PVE oils are a whole different animal. POE, especially, is hygroscopic; it absorbs moisture and is more chemically active. It not only breaks down when exposed to water (hydrolysis), but it also acts like a detergent for copper oxide, scrubbing it off the pipe walls and carrying it straight into filter-driers, strainers, expansion valves, and tiny oil ports. That oxide may take days or weeks to fully clog something, but once it does, the customer is stuck with restrictions, loss of capacity, and often premature compressor failure.

The only real defense is to keep the oxide from forming in the first place by purging with nitrogen during brazing. Skipping it doesn’t save much time. It just delays the problem long enough for someone else to deal with it.

Moisture In the System

Moisture control used to be more forgiving. With mineral oil, a little water didn’t set off a chain reaction. But with POE, even small amounts lead to acid formation. Those acids leach copper from tubing and windings, and that copper often plates out where it shouldn’t—inside bearings and on valve surfaces.

This isn’t an overnight failure. It’s a slow decay of the system’s internals. Over the years, the wear and tear add up to locked rotor, damaged windings, and reduced efficiency and capacity. The tech who “saved time” by pulling a shallow or incomplete vacuum never sees the failure; the customer just gets an expensive replacement bill years earlier than they should have.

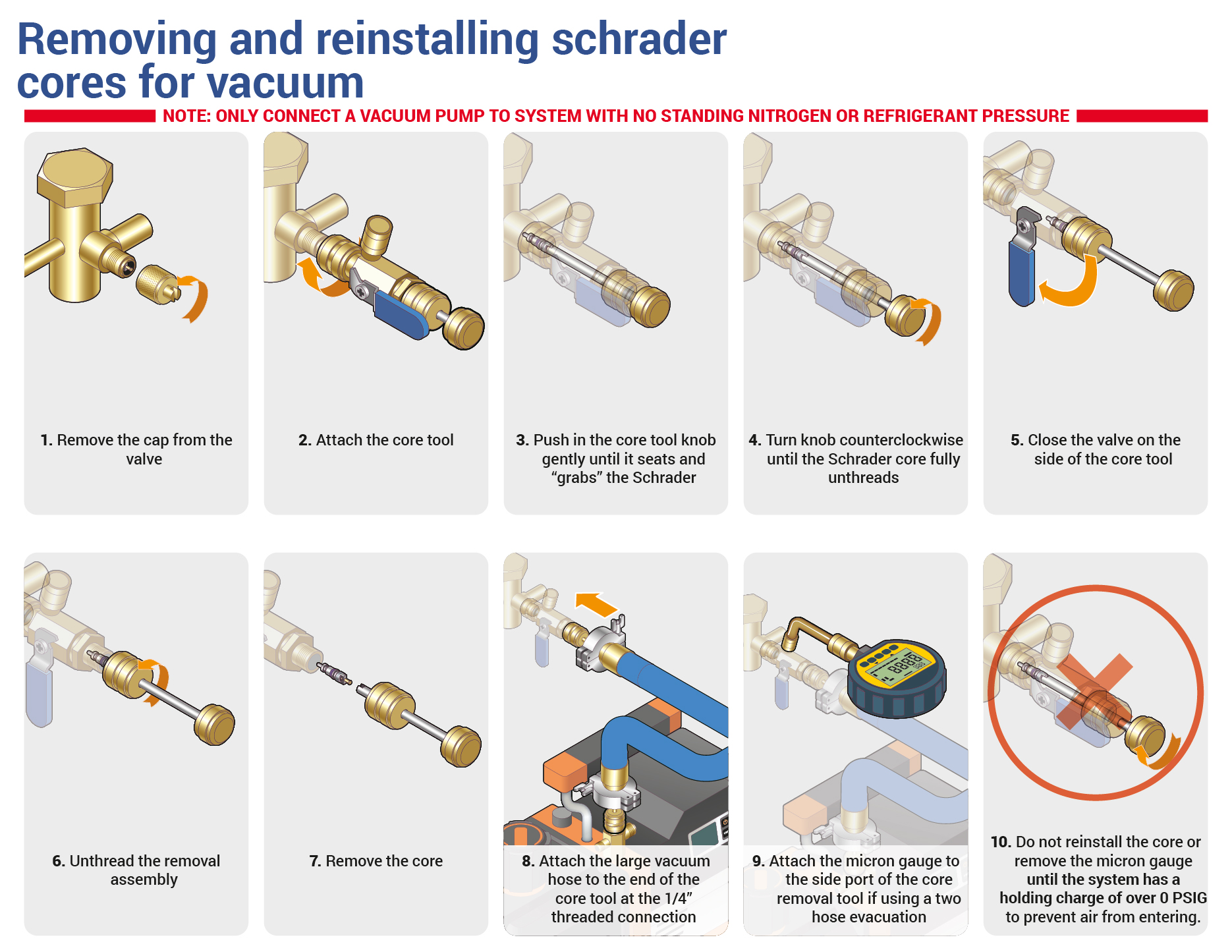

Skipping a Proper Vacuum

In the past, refrigerant was inexpensive, EPA rules didn’t exist, and many technicians simply “purged” lines with refrigerant instead of pulling a true vacuum. That bad habit carried over for some people, but today it’s a different world.

Now that we’re dealing with A2L refrigerants, the presence of oxygen in the system adds another layer of risk. Combustibility aside, oxygen in the refrigerant loop can cause chemical breakdown of both oil and refrigerant, leading to restrictions, efficiency loss, and shorter compressor life. A proper triple evacuation and a decay test aren’t just “best practice” anymore — they’re required to give the system a fighting chance at a full lifespan.

Airflow Setup

A system will still blow cold or hot air with airflow that’s too high or too low. But wrong airflow quietly robs performance and comfort over the life of the system. Too high, you lose latent capacity in summer or cause drafts in winter—the system can’t dehumidify well, which shows up on muggy days or during shoulder seasons. Too low, you risk coil freeze-ups, high compression ratios, and overheating compressors and tripping limits.

The worst part? The customer often doesn’t even know airflow was the problem. They just assume “this is how air conditioning works” and live with high humidity, poor comfort, or high power bills for 10+ years.

Control Staging

Multi-stage equipment is great—when it’s set up right. But if the staging controls are wrong, the system may never move into high stage, or it may stay in high stage constantly. Either way, it’s wasting capacity or efficiency.

This is one of those mistakes that can plague the equipment for its entire life. If the customer doesn’t complain, it never gets caught. They just have a system that runs worse than it could for as long as they own it.

Combustion Analysis

A furnace can run for years, producing dangerous levels of carbon monoxide without any immediate issue, until something changes with the venting or pressure conditions in the space. Then that CO can spill into the living area.

Even when safety isn’t the issue, combustion that isn’t tuned correctly wastes fuel. That’s extra money out of the customer’s pocket every heating season. Skipping combustion analysis isn’t harmless just because no one has gotten sick (that you have heard about).

Charging Shortcuts

Charging by “good enough” instead of weighing in and using superheat/subcool methods can quietly damage a system. A compressor running hot from a low charge or flooded from an overcharge may keep going for years, but it’s running harder and hotter than it should, wearing itself out from day one.

Worse yet, things like dumping liquid refrigerant into the suction during startup can wash out lubrication in those critical first moments. The compressor may survive, but the damage is baked in for the rest of its shortened life.

Disconnecting or Failing to Install Crankcase Heaters

A crankcase heater isn’t there for decoration. It prevents refrigerant from migrating into the compressor during the off cycle. If you disconnect it, the oil can foam on startup, causing a momentary loss of lubrication. One incident isn’t usually fatal, but repeated cycles like that shorten the compressor’s life. The customer pays for the replacement years sooner.

Other “It Still Works” Habits

There’s a long list of these slow-burn mistakes: undersized conductors that run hot for years, uninsulated horizontal drains in humid climates that foster biofilm growth, duct systems with high static pressure that require the blower to draw higher current, condensing units installed with inadequate maintenance clearance, and more.

Each of these can work “fine” in the sense that the system turns on and blows either cold or hot air. But “fine” just means the customer is paying the price in hidden ways: higher bills, more frequent repairs, or shorter equipment life.

The Bottom Line

When you skip best practices, you aren’t saving the customer anything. You’re gambling with their money, their comfort, and their safety. The fact that you didn’t get a callback doesn’t mean it “worked fine.” It just means the cost was slow, hidden, and paid by someone else.

If we take pride in our work, we can’t hide behind “I’ve been doing it this way for 20 years.” The right way is the right way, even if no one ever knows you did it.

—Bryan

Comments

To leave a comment, you need to log in.

Log In